Over a year ago, my father invited me and my family to come to Maine for the solar eclipse. I said yes, thinking both that it was a magical idea and because at that point it seemed impossibly far away. Before April 8, 2024, I would have a new baby. It would be springtime, and therefore easier to be with children in Maine.

As the date approached, it began to bear down on me. I say “bear” because I am always having dreams about bears surrounding the Maine house, making it impossible to go outside. I always dreaded seeing my father. His mind, his presence, would shrivel mine. Everything tended to decompose around him, whether from lack of care or his intentional unraveling. Actually, better than “everything decomposed” would be “everything denatured” — like enzymes breaking apart, becoming impotent and fragmented. He was often on drugs. The house was covered with more than a millimeter of dust. Was he violent? The question was alive enough in the air that I could not bring my children to be with him. I was afraid my son would catch a disturbance. I was afraid that bringing my infant daughter on the two-and-a-half-hour-drive to the Canadian border to reach the “path of the totality” with my dad would result in disaster. What would happen? Nina would scream and my father, unable to stand it, would open the door of the moving car and roll out onto the side of the road. And I didn’t want to be with him, alone.

So on March 14 I called him and cried and told him I thought it was a magical idea to see the eclipse together — an idea, in fact, that conjured the firmament-loving nature of my dead mother — but that I couldn’t make it work, my kids were simply too little. And he told me not to be upset and that it was ok, and to come for a week in the summer instead. I was so relieved and surprised that he still had it in him to be fatherly with me.

I am not ready to write about what happened between then and March 17, at 2:16 p.m. when I got the last email from him, “don’t ask me where I went I don’t know either.” Actually I’m not ready to write about what happened after that, either. But I couldn’t let the day of the solar eclipse go by without marking it, and the thing that I’m best at is writing so here I am.

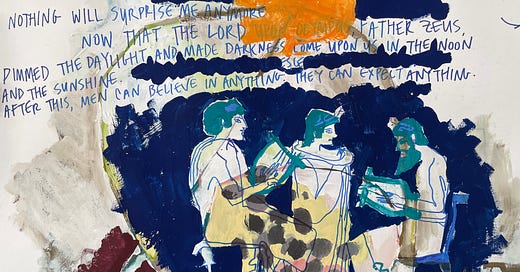

I went to the Second Story Books warehouse in Rockville a couple of days later and picked up a book of ancient Greek lyric poetry. Lo, just a couple of pages in is a poem by Archílochus of Paros (~680-640 B.C.), an amateur poet, titled “Eclipse of the Sun”:

Nothing will surprise me any more, nor be too wonderful

for belief, now that the lord upon Olympus, father Zeus,

dimmed the daylight and made darkness come upon us in the noon

and the sunshine. So limp terror has descended on mankind.

After this, men can believe in anything. They can expect

anything. Be not astonished any more, although you see

beasts of the dry land exchange with dolphins, and assume their place

in the watery pastures of the sea, and beasts who loved the hills

find the ocean’s crashing waters sweeter than the bulk of land.

The day turning dark, ocean beasts on dry land, enzymes denaturing, reality twisting and perverting, seeing letters and words in the sky. “After this, men can believe in anything.” The expansion of the realm of what’s possible is the destruction of meaning. If the sun ceases to shine, nothing is certain anymore. There are moments when a wall is demolished in our minds and the wind blows through and we blink with confusion. I’m still blinking with confusion. I am wondering if anyone will understand the connections I’m trying to make.

I’ve spent a lot of time wondering if I can “look right at it” — the violence of his suicide. Can I consider it unflinchingly? The Washington Post cautions me against looking directly at the eclipse. I will probably look and then quickly look away. Skimming it like a water bug but not letting it touch me. One of my father’s most persistent symptoms was fear of light. At times of high stress, he would become psychotically blind and wrap a scarf around his eyes. At one point, he predicted there would be “mass death” during the eclipse. Well, it turns out the death he was predicting was his own.